Writeup of Technical Challenge - Integration

Recently I applied for a software engineering position in a team that does integration between third-party software and a proprietary system. One of the stages of the selection process was a take-home challenge that, as I undertand, mimics a lot of what is done on a day to day basis on the job.

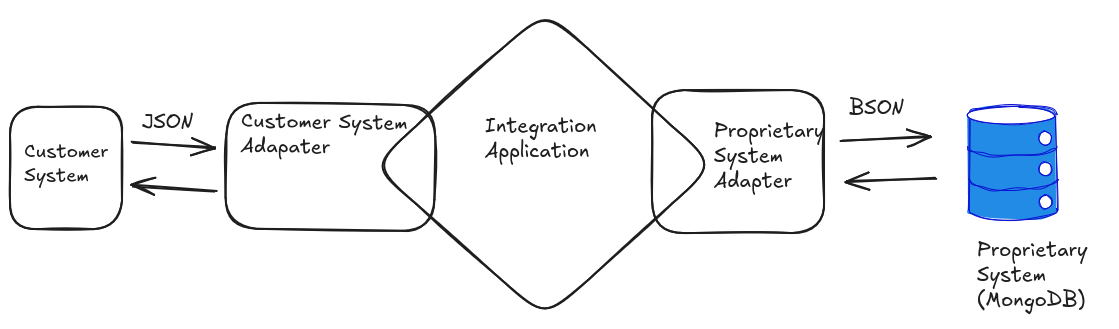

We have two systems: a customer system (let us call it CS) that reads and writes JSON and the proprietary system (PS) represented by a MongoDB instance. The missing link is the software I had to write, the middle layer: a program whose responsability was to translate and sync messages from CS to PS and vice-versa. The challenge was to write such program in a fashion that would make it simple to add other third-party systems in the future. Extra points for error handling, clear logging, testing.

The language used in implementation was Python. I already has some experience with it, but man… did I learn a lot with this challenge. This post is to talk about the main learnings I had.

1. The architecture

First of all, it is import to say that I still do not have professional experience with software development. This means that most of my projects did not have to have a very complex architecture. Modular code: OK. But not architecture. This was the first time that I had to stop and think about it. Also, I read a lot about architecture, but it never really “clicked”. Until this challenge. The image below synthetizes what I implemented:

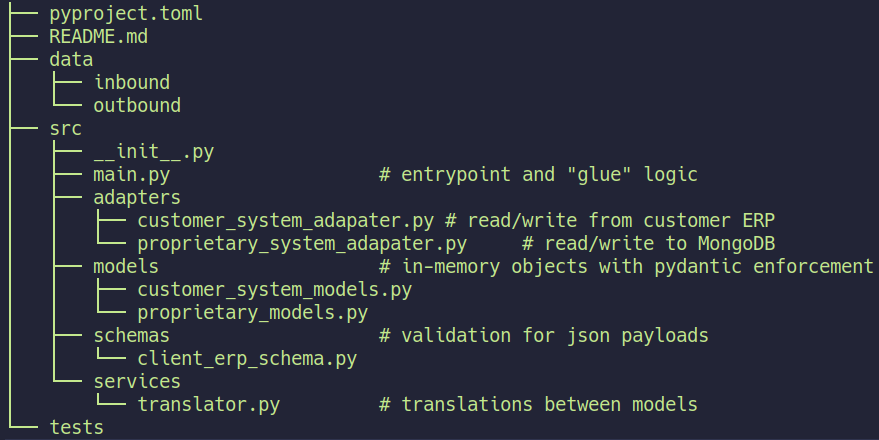

The directory structure of the project was as follows:

src/adapters/customer_system_adapter.py defines a class called

CostumerSystemAdapter whose only jobs is to read json and write json.

Similarly, src/adapters/proprietary_system_adapter.py defines class

ProprietaryaSystemAdapter whose only jobs is to connect to the MongoDB

instance and interact with it retrieving and sending data when necessary.

We used Pydantic library to instantiate in-memory objects from the JSON read from CS and BSON read from PS. Pydantic makes it very easy to guarantee that an instantiated object will follow strict rules (like having datetime attributes that are UTC-aware).

The translation between system occured in src/services/translator.py.

So, in case a new third-party system was to be add, we needed:

- An additional adapter

- An additional pydantic model

- An additional translantion from and to the new pydantic model

- Adjust the

src/main.pyfor the newly added classes and functions

We would not have to touch the previously defined adapters and pydantic models.

In big projects, we could even define an Abstract Base Class (Python’s attempt at interfaces) in order to formalize what methods should be implemented in order to have a valid adapter for new systems.

2. Pytest fixtures

One of the deliverables was an end to end test using Pytest. I had already managed

to implement an end to end test using a python script to generate sample data, a

docker-compose.yml to instantiate a MongoDB database (and collection, aka

table) and a Makefile to “orchestrate” everything. However, I did not know how

to do that using Pytest.

Then, interacting with Claude Sonnet 4.5 I began to understand a little bit of Pytest Fixtures. They are user-defined contexts that can be used in tests (they are passed to test as parameters). We can use fixtures to define custom values for environment variables, as well as set connections to mocked databases.

So, to perform and end to end test using Pytest, all I had to do was to write a fixture that generated sample data and connected to a mock database, pass this fixture to the test and then call the program entrypoint from the test. Then pytest did its magic to organize output and report it.

3. Decorators

Just like architecture, I had already read about decorators and their usefullness. However, I had never encountered the need to use them in any of my projects. Until now.

As said above class ProprietarySystemAdapter contained methods to connect and

interact with a MongoDB instance. One of the requisites of the technical

challenge solution was to have some resilience policy with regards to the

database. So, if the connection between the program and the database was lost

for a brief moment, the program should not crash - it should try to reconnect a

number of times before declaring a critical failure.

To handle connection with MongoDB, I use Motor, an async Python driver.

So, at every method that interacted with the database, a potential connection

failure could occur. Naively, I had to write try/except blocks in every method

to handle this potential problems. This is where decorators enter the scene.

A decorator is a function that takes a function as a parameter and returns a new function. This means that it is a way to add behavior to a previously defined function without having to rewrite said function.

In our case, I wrote a decorator to handle with connection issues and then I “wrapped” all methods into this decorator. This saved a ton of lines of code and made it much more elegant. Decorator definiton is below:

def retry_on_mongodb_error(func):

"""Decorator for MongoDB error handling with one extra retry"""

@wraps(func)

async def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

try:

return await func(*args, **kwargs)

except PyMongoError as e:

logger.error(f"MongoDB error in {func.__name__}: {e}")

logger.info(f"Retrying {func.__name__}...")

try:

return await func(*args, **kwargs)

except PyMongoError as retry_error:

logger.error(f"Retry failed: {retry_error}")

logger.critical("Shutting down due to MongoDB errors")

sys.exit(1)

return wrapperAnd then, we used it to wrap functions:

@retry_on_mongodb_error

async def check_connection(self):

await self.collection.find_one({}, projection={"_id": 1})

logger.info(

"MongoDB instance, database and collection are recheable. Proceeding..."

)Conclusion

I learned a lot and am happy that I took the time to write this post. Here’s to hoping that I get this job. 🤞